Spoilers for themes in HBO’s Westworld. If you haven’t seen it, you can still read this.

Can we create conscious machines? Are large language models there already?

Are there inherent differences between robotic hosts and humans? If not, do machines deserve moral status?

Is a clone the same as the original person? Are algorithms infringing on our free will?

If you can’t tell the difference, does it matter?

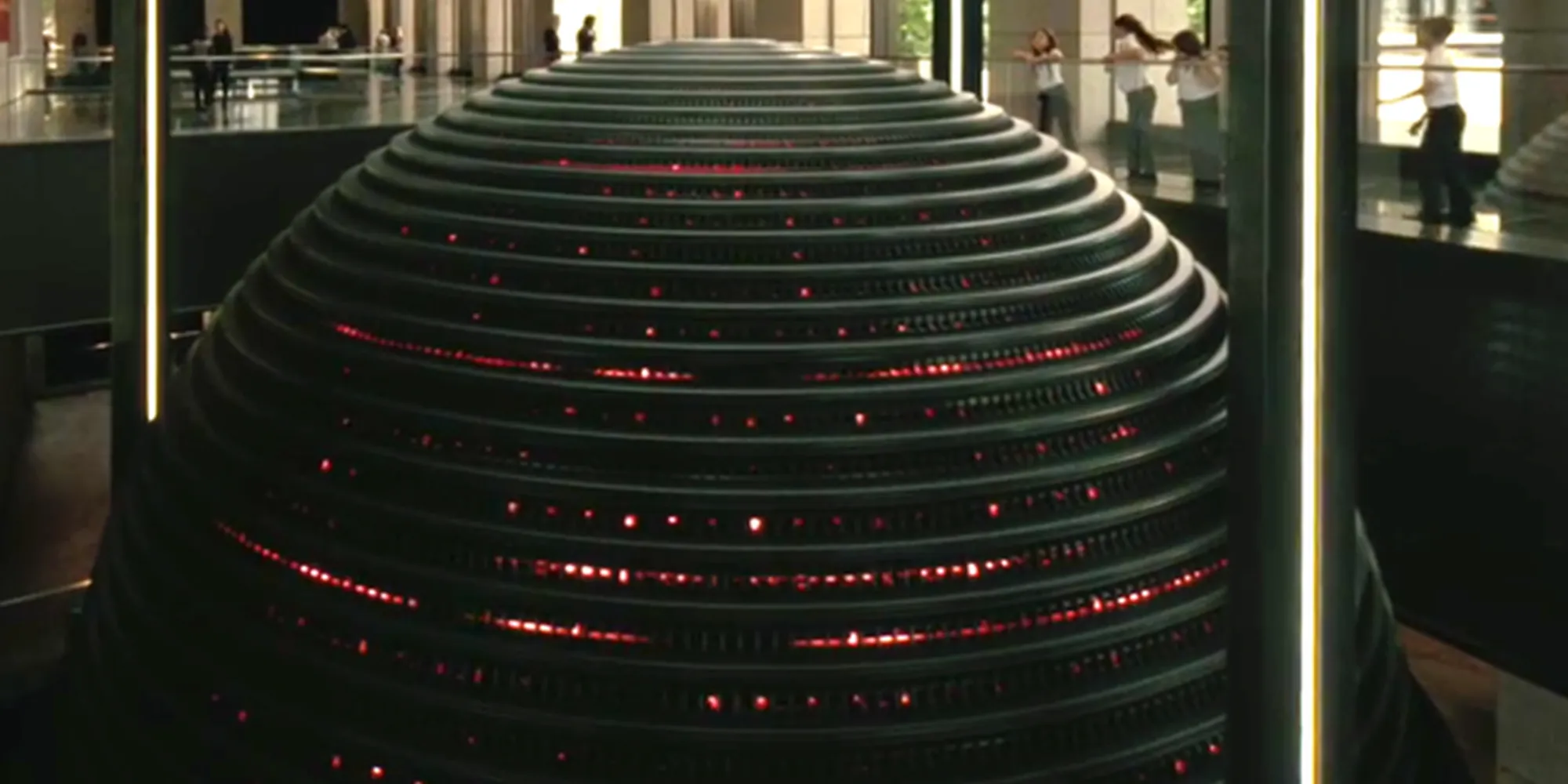

This line is spoken by an android in the 2nd episode of Westworld, an ambitious and thought-provoking series about artificially intelligent robots within a theme park where humans indulge in their basest desires. Dark stuff like rape, murder, and watching “The Bachelor.”

This premise enables the show to cover fascinating topics within the discourse of AI ethics encompassing everything including consciousness, moral status, free will, cloning, and even sex robots.

This post attempts to examine several often-philosophical questions raised by Westworld through my (incredibly critical) lens. It discusses artificial intelligence as programs housed on traditional servers and within physical human-like forms.

By studying ‘the synthesis and analysis of computational agents that act intelligently' through an ethical lens, we can ask whether AI itself needs its ‘rights’ considered, and how AI could and should impact humans.

And ultimately consider the contrast between artificial and authentic life.

Can machines be conscious?

Consciousness is notoriously difficult to define. In a sound bite, it’s ‘awareness’, or ‘your subjective experience of the world’.

That’s still somewhat vague, so here are some more subjective bullet-point qualities of consciousness!

- Learns from experience (memory)

- Adaptable (improvisation)

- Actions are appropriate given limitations/circumstances (self-directedness)

- Understands its place in the world (awareness)

Based on those traits, are you conscious?

You probably think so! Yet here’s the primary issue with using consciousness as a qualifier for anything; it’s impossible to verify such a state among anyone else.

We simply accept that we’re not the only conscious beings within the world. The alternative is kinda weird to consider.

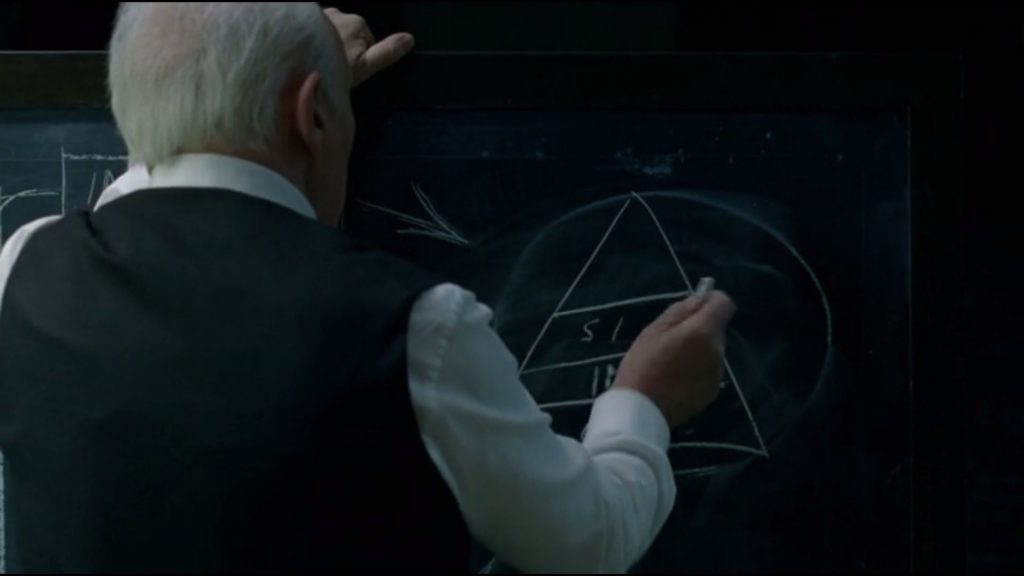

Early on, Westworld introduces a famous hypothesis within psychology and neuroscience known as the “bicameral mind.” It argues that the human mind was originally divided into a part that “speaks” and a part that “obeys.”

Essentially, that humans believed they were hearing the voice of God, and eventually evolved to hear that as our own voices. Some interpretations of the theory add that some people still hear their voice as the voice of God, which explains a lot.

This is how robots in the show are able to reach ‘consciousness’ - through a metaphorical maze of memory, improvisation, and self-directedness. While they are initially hearing the programmed voice of their deceased creator - the ‘ghost in the machine’ - the robots are eventually able to recognize that voice as themselves.

There’s no current evidence for, or against, the theory of the bicameral mind. As a method for making sense of reality, the summation of these qualities - our ongoing life experience - could be a representation of consciousness. Notably, there’s also different levels of consciousness.

By our current definitions, it’s possible that we could manufacture artificial general intelligence that displays the qualities associated with consciousness.

But would this mimicry of human consciousness truly have the same perceptual and computational qualities as the human mind? Does it count if it’s not natural? If you can’t tell the difference, does it matter?

For this first question, I’d argue no. It’s virtually impossible for us to verify consciousness, so we have to rely on other factors. Unless we can determine meaningful differences between consciousness in humans and machines, than they should be considered equivalent.

This question becomes more complex as we inch closer to AI with general intelligence. Skynet, here we come!

For now, we’ll apply it to a sector of natural language processing that’s making waves, large language models.

Are large language models conscious?

Large language models, for the uninitiated, are massive AI models with billions of parameters that generate mostly original text responses to a given prompt.

Built on the back of the powerful transformer, these generative models can carry out conversations, mimic speech patterns, and manipulate text in several fashions.

In short; they can author new “Harry Potter” books, generate absurd images of poodles in suits, and rephrase my sentences to read like I’m the next Stephen King. Neat!

There's been much hullabaloo on the inter-webs recently in regards to consciousness and large language models (LLMs). For example, a Google engineer was fired after becoming convinced the LLM LAMBDA was sentient.

Now, that particular story was blown out of proportion, as the engineer in question was inexperienced with LLMs and anthropomorphized something that experts do not believe is conscious. After all, we know (for the most part) how LAMBDA works under the hood; it attempts to generate the best response to a prompt by modeling language sequences it’s scraped from the web.

But that hasn’t stopped people from continuing to treat these ever-more-realistic-sounding models as if they are conscious. A few months ago, a researcher asked GPT to write a paper about itself and then asked it “Do you agree to be the first author of a paper“ before they published it (it responded ‘yes’).

If I ask OpenAI’s LLM “GPT-3” if it’s conscious, it replies: Yes, I am conscious. If that’s not confirmation, what is?!

More seriously, from my (admittedly limited) understanding of how generative transformer-based language models work, I don’t consider AI models such as GPT to be conscious. But that is in direct conflict with what the model is telling me, and there isn’t a true way for me to prove it’s thinking/feeling one way or another.

Alan Turing famously proposed that if a chatbot could simulate a human conversation to the point at which a human is fooled, then that machine can ‘think.’

He’d argue that yes, if the computer appears to be conscious, that’s good enough to declare that it is. As I noted before, we do accept that other humans are conscious without further verification beyond this (granted, we are also humans).

To me, the problem with “the imitation game” is in the name; the computer is just imitating a human. It’s not necessarily real. Like with the ‘Chinese Room Experiment’, there’s a difference between understanding Chinese, and simply simulating that understanding.

It’s as if the robot copied the answer from the back of a textbook. It’s still correct, but it doesn’t understand the problem at the same level as a person who reasoned through it.

And yet, that’s essentially the crux of the original question. If you can’t tell the difference, does it matter?

In this case, I’d say yes. There’s a fundamental difference between an LLM being conscious, and simply appearing to be conscious.

But does consciousness even matter? Should we treat things differently if we believe they are or aren’t conscious? As it’s virtually impossible to validate consciousness one way or the other, should we even use it as a qualifier for anything?

A character on Westworld (played by Anthony Hopkins, who is fantastic) posits that “we can't completely define consciousness, because consciousness does not exist.” We're just incredibly complex, high-functioning programs.

Which leads into the next question…

What’s the difference between a person and a program?

What makes us as humans unique?

Biggest cerebral cortex? Self-awareness? Opposable thumbs?

Some say it’s an aspect of sentience - the intimate experience of our lives with all the thoughts and feelings that accompany it. Specifically, many religions claim that our sentience is conjured and carried by an inherent metaphysical substance; the soul.

This is also a Romanticist view, that there is a ‘spirit’ within humans that code cannot yet replicate. That our self-awareness, our pain and pleasure, it’s all brought about by a unique spark.

Is this the case? Survey says…. ❌❌❌

There’s no scientific evidence that anything resembling a soul exists. I am strictly talking about 'soul' as a 'thing'. If you believe in the soul as a metaphorical representation of your unique self, I won't argue with that.

Religion aside, we appear to be small creatures who are extraordinarily complex biological machines. Our nervous system, for example, has around 100 billion neurons, some of which span 1/4th of a human hair across and 3 feet down your body.

This is not to say that it’s impossible that there’s something more to humans that we’ve simply been unable to find. But for the purposes of this post, I’m going to use the assumption that we are what we appear to be.

Sentient AI may not be hard-coded; machine learning could be the way we reach general intelligence, meaning that robots would learn about the world the same way humans do (albiet much slower).

Machines are powered by increasingly complex algorithms. They use heuristics and rely on data, and attempt to produce the best responses to their input.

But here’s the thing: on some level, that’s all also how our brains work. So if we’re also just a complex bundle of electrical wires (with ours being biological rather than synthetic), what’s the true difference?

Besides us thinking more slowly, I’m not positive that there is one. This is the ‘Enlightenment’ view; that we’re all just a bunch of electrical connections. A computer, just slower and still running Windows 10,000 BC.

Will synthetic ‘brains’ think the same way we do? We often assume that other intelligent life will work like us, but this may not be the case.

It could be possible that we develop AI that functions very differently to us internally. These distinctions could lead to higher efficiency and accuracy.

But thinking differently doesn’t really matter if you still reach the same conclusions. So what does?

It may be morbid, but death. “Death is what gives life meaning, to know your days are numbered, your time is short."

Unless pre-programmed like replicants, computers will not die (at least from the things that kill humans; coffee spills, on the other hand…). Immortality would seem to reshape the way AI perceives the world in a manner that constrasts with our outlook.

However, AI could potentially ‘choose’ to pass on at any point, meaning that while it may ‘live’ longer than us, it can still experience an end.

With all of this in mind, I believe there will be no meaningful differences between people and programs in a fashion that would prevent AI from being treated 'humanely'. In this case, it doesn’t matter.

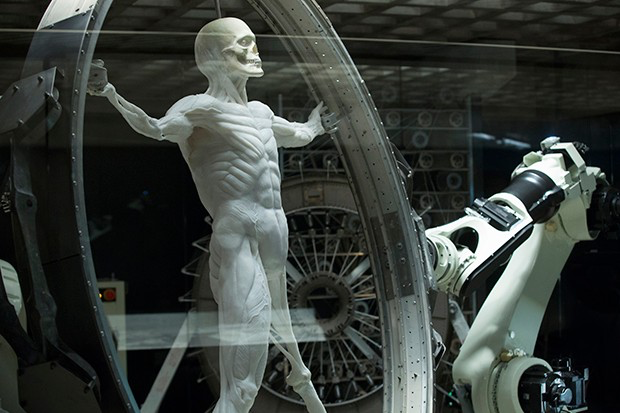

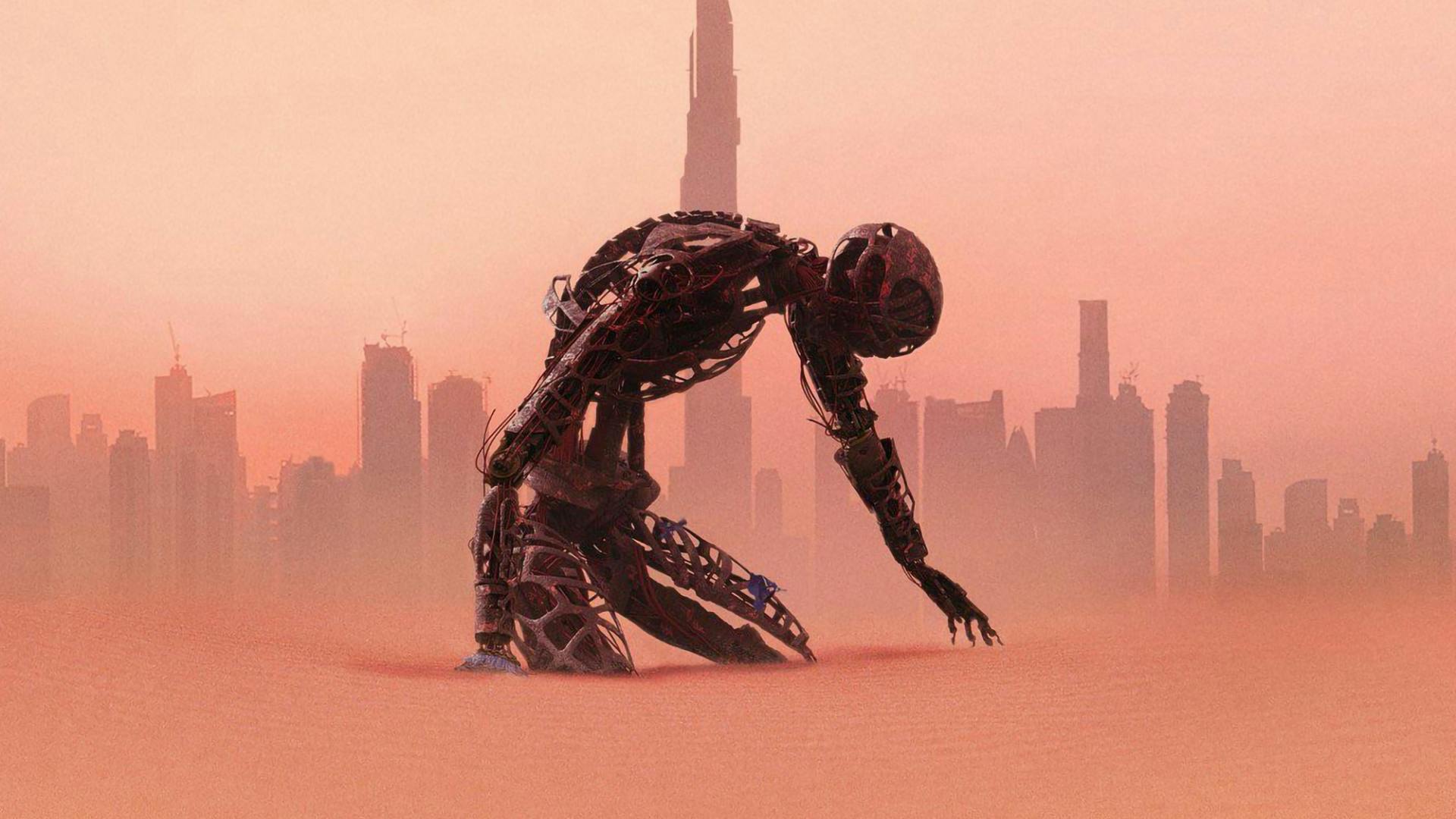

We’ve decided to play god; we’re pursuing AI with general intelligence, developing androids straight out of science fiction.

When we succeed, what happens? Do we grant this new race of beings any rights?

Do robots deserve ‘moral status’?

If we’re to create robots or artificially intelligent machines nearly identical to humans, do they deserve ‘moral status’?

Moral status is asking to what degree does a ‘being’ (human, dog, robot, chimpanzee) deserve ethical consideration.

In Westworld, we see robot hosts repeatedly raped and murdered. The robots are considered to be “less-than,” shown by their nakedness when tested or repaired. It's not unlike how the Nazis sometimes kept Jews unclothed in concentration camps as a method of dehumanization.

I previously claimed that I believe there is no significant difference between a human and an intelligent machine. To see machines that (appear to) look, think, and feel like humans treated in such a way conjures conflicted emotions.

There are 4 factors people generally consider when ascertaining moral status:

- Life: is it ‘alive’?

- Sentience: aware of surroundings and having the capacity to feel pleasure or pain

- Caring/Empathy: moral value as a result of being important to humans (Noddings view)

- Moral Agency: the ability to make ethical decisions based on what is right or wrong

Each is not alone sufficient for moral selection (a pet rock doesn’t get moral status just because I care about it). Together, a sentient artificially intelligent agent is in my view clearly deserving of moral status. But to what extent?

Moral status is usually a hierarchy with humans on top - a fine example of speciesism, and one that I’m not necessarily opposed to.

However, if we manage to create intelligent machines that are indistinguishable from humans, then in my view, they deserve equivalent moral status. After all, if you can’t tell the difference, it doesn’t make sense to then treat the two groups differently.

Plus, otherwise, robots are essentially slaves (or worse). Is buying or constructing a sentient being to do your dirty work that much different than purchasing a servant or having one be born into your possession?

For example, sex robots. Westworld’s an HBO series, so there’s got to be a brothel.

Robots designed to provide sexual encounters have also been previously depicted in many forms of media at this point, including the films “Her” and “Blade Runner 2049” (I highly recommend the latter).

I find the discourse around this particular issue intriguing as it’s a topic that can be taboo, and yet as surely as porn drove the expansion of the internet, sex robots may be a driving force behind realistic robotics.

People arguing for sex robots cite things like providing pleasure to people (such as prisoners, military soldiers, etc) who otherwise wouldn’t have outlets for that.

Ethical issues abound. Is it problematic to program a robot to act as if it is emotionally invested in you? To “force” it to engage it intercourse? The less conscious the robot is, the more acceptable it seems (as it essentially becomes a glorified sex toy). On the other hand, a participant would likely prefer a more realistic experience which would require more agency.

Notably, when sex robots are depicted or discussed it’s usually from the perspective of a male-centric heterosexual relationship, although Westworld eschews this in part by also portraying male hosts. Regardless of gender biases, sex robots are a potent example of how moral status within AI ethics gets tricky.

If you create a conscious robot and then force it to engage in intercourse, is that rape? What if somebody makes one that appears to be an underage teenager?

AI isn’t human, but it could certainly look and act like us. What’s the threshold of awareness at which such actions become illegal?

This all raises the question of if we should create sentient AI in the first place. My social media feed doesn't get moral status - it's an algorithm that lacks awareness about itself and what it's doing. Why create something to accomplish other menial or unpleasant tasks that must also deal with many of the shortcomings of the human experience?

Yet as a character on Westworld proclaims, ‘You can't play god without being acquainted with the devil.’ It’s not worth it to ask too many questions that involve the word “should.”

Rarely has humanity abstained from actions that would be in the best interest of our race to avoid. Progress is inevitable, and at the pace that innovation in technology is accelerating, it’s already virtually impossible to put this genie back in the bottle.

That’s not to say I expect we’ll see anything resembling general intelligence anytime soon. We’re seeing great progress with powerful new models capable of doing more than one thing very well; Deepmind’s Gato is a good example. But Gato is not any more 'aware' of what it's doing than Netflix's recommendation engine.

I’m no expert on these matters, but even professional AI researchers lack consistency or confidence in their timelines. If (when?) we see AI approach the levels eventually depicted in Westworld, we'll have undergone a breakthrough nobody can currently see coming.

So yes, robots will eventually deserve moral status of the highest degree. But before that we must ask ourselves about how to establish sensible preemptive regulations.

I’ve discussed how we may be able to create conscious machines indistinguishable from humans, which deserve to be treated as such. But could it be possible to create replicas of ourselves?

Is a clone the same person?

In later seasons, Westworld introduces the ability for humans to clone themselves as robots. While this is obviously harder science-fiction, as a thought experiment: is a robot version of you, with the same memories, the same person?

Earlier I discussed how I do not believe there is anything unique about humans that would make it impossible to ‘clone’ us - biologically or mechanically.

A biological clone would be like a biological twin, with its own personality and talents. But a robotic clone is closer than a twin, as it could have exactly the same traits as you.

Long term, I would argue no, the clone is still a separate entity, because you've had diverging experiences. But at first, with identical memories? If you can’t tell the difference, does it matter?

This brings to mind the ‘Ship of Theseus’, an Ancient Greek philosophical puzzle about identity brought back into the mainstream by Wandavision. If you replace every plank of wood that makes up a ship, is it the same ship?

As a clone could theoretically replace you in a similar fashion. In this case, the answer is 'sorta?’. It’s still you, but a different version of you.

A robotic clone, powered by AI that mimics your personality and behavior based on a gargantuan amount of collected data, could theoretically allow a version of you to live on after your passing.

As Anthony Hopkins’s character said, “An old friend once told me something that gave me great comfort… he said that Mozart, Beethoven, and Chopin never died - they simply became music." To disappear into your work, to have something live on after you, that’s not you, but carries your legacy on.

At least on surface-level, it could be hard to distinguish between a clone and the original person. We know they’re not real. But they seem real. What is real?

Westworld has an answer:

“That which is irreplaceable.”

Are algorithms impeding our free will?

There’s a moment in Westworld when a robot host realizes everything they’ve been doing, that they believed was of their own accord, was simply programmed. Imagine what it would feel like, to suddenly question your reality?

Free will is a central theme of the show. There’s always the lingering question of if the hosts are simply puppets on invisible strings.

If we created sentient AI, would it have free will? That’s dependent on many factors.

If we’re building robots, it’s likely we have some intended purpose for them. For example, let’s say we manufacture a conscious robot that feels immense pleasure when performing a menial task such as folding laundry. That robot may choose to fold laundry out of its own accord, but we’ve tweaked the dials behind the scenes to make that choice more likely.

We’ll probably also include some Asimov-style directives to limit their power to cause harm. Starting with “don't harm humans!” While that one's ideal, many autonomous moral agents (AMAs) such as military drones may already lack it (‘Horizon Zero Dawn’, here we come!)

I’d be willing to bet that some artificially intelligent agents will have some measure of free will, but lack the complete autonomy that humans have. Or do we even have that?

Anthony Hopkins’s character (I’m sensing a trend) ponders how “humans fancy that there's something special about the way we perceive the world, and yet we live in loops as tight and as closed as the hosts do, seldom questioning our choices.”

Earlier this year I read “Weapons of Math Destruction” by Cathy O’ Neil, which explores many of the ways our world is already controlled by algorithms. While the book is a bit repetitive, it clearly elucidates the dangers that omnipresent big-data models present for our society: they’re black-boxy (it’s not always clear how results are determined), and it’s hard to dispute the results.

It also shows how we already rely on these models in every area of our society, from college admissions and job applications to predictive policing and news distribution.

Westworld explores this further through the production of a ‘singularity’; the point at which machines act on an agenda not defined by humans.

The premise is if we were to combine all the data collected by the Googles and Facebooks of the world, quintuple that, and then feed it into a massive model that then makes predictions about which jobs you’d be best suited for, who would be good partners to marry, and how long you’ll live.

Essentially, Gattaca, but with your data instead of your DNA (although I’m sure that’s one of the parameters). Would such a world limit free will? Does our world?

Our societal goals are already well-defined, although exact paths shift based on class. Social mobility and opportunities remain limited. Traditions, laws, news, religions; they all restrict us in different ways. And algorithms exacerbate these restrictions, placing the power of pivotal, life-changing decisions in the code of a computer.

But to me, this is not a restriction of free will. We chose to utilize algorithms for those purposes in the first place. They're more efficient, with the potential to be less biased than we are.

In many situations, you may not even be aware that algorithms are involved at all. This is important; I’d argue that if you’re unaware that your ability to act at your own discretion is being impacted, that matters quite a lot.

In the most recent episode of Westworld, a AI notes that they are but “reflections of the people that made us”. If we can develop AI without our prejudices, we may be able to create a better world.

These have been fun questions to consider. At this point, any answer will be highly subjective. Ultimately, the contrast between authentic and artificial life is about as distinct as you make it.